Folk Medicine, Herbaria, and Religion of the Ancient Italian Peninsula With Emphasis on the Etruscans and Their Pantheon

Well, here it is- the essay that was requested to be published!

The following is a 7,000 word essay on the Ancient Italian Peninsula with emphasis on the Etruscans. This essay was an assignment for school in which I had to research an indigenous culture, their herbal medicine, their relationship to nature, animals, plants, how both men and women prepared medicine, the pantheon of this culture, and their perception of the universe. We will learn that the Etruscans may have been the indigenous people of Italy, however, very little is known about them. I have a connection with these ancient people, and I was guided to do this essay on them. This was my first assignment, and it was created over the course of a year. Since the submission of this work to my teacher, there has been more information that has come to light, as my research of the Etruscans is forever ongoing. With that being said, some of the content in this essay may be dated. I added some new information, but to really continue to deep-dive into the Etruscans would take up a considerable amount of time. I, however, was happy to return to this essay as the Etruscan Pantheon feel like old friends to me. If you learned something from this essay, or want to support me and my work, I am leaving a link below where you can donate and support. This fund is going towards anything I need to continue my work and practice for school, as well as the diploma courses that are available to me after I graduate. Please enjoy this essay!

Of note: this will the last deep-dive I will make outside of a paywall. I am moving towards making this substack an extension of the blog The Mad Sorceress Grimoires. After this, this substack will help to create a space where I can stretch myself a bit, and share even more content with you all. Please consider subscribing.

What type of content will you find in the subscription?

Herbal Monographs with their chemical constituents and planetary rulership. Bonus: My own experience with certain herbs.

Medical Astrology musings

Phytonutrients: the lost language between plant and human

The Zodiacal Color Wheel

Flower Essences

Hypnagogic and lucid dream experiences

Recipes [food + herbal]

Messages from meditation, dreams, and work with my personal deities

Tarot readings

Star chart readings

Herbal, Healing Food, and Self-care ideas for Creatives, Artists, and Magicians.

Connecting Science & Spirit

Preface

As I was researching information for this assignment, I was propelled on a side-quest to explore my ancestors. Years ago, I traced both my maternal and paternal bloodlines with DNA testing, and cross-referenced this testing with the knowledge that was passed down to my family orally about our ancestry. I am a 3rd-generation Sicilian/Italian-American on both sides of my family, and both sides of their families, and so on and so forth. Specifically for this assignment, I began looking into my ancient ancestors, and I found I have exclusively Mediterranean ancestry: Cypriot, Anatolian, Mesopotamian, Iranian, Levantine, and Egyptian. There is also a possibility of very small amounts of Romanian, Balkan, Finnish, and Bangladeshi. I am listing them all, because I think it is important to name your ancestors, especially because I believe this work was mostly driven and guided by them. Regardless, deep-diving into this ancestry bolstered the dedication to writing this essay, and vice versa.

This essay will focus mainly on the Italian Peninsula, however, I cannot speak of ancient Italy without mentioning the Etruscans, whom I believe are also my ancient ancestors. It is because of the research I had started for this essay that I was even introduced to the Etruscans, and fell in love with learning about them. This mysterious group of people are thought to be the native people of Italy. Little is known about them, and there is a lot of debate whether they actually were the native people of Italy, or if they may have been “sea-faring people”, who ended up on the Italian Peninsula before the Greeks and Romans. For a bit more historical context, Etruscans were referred to as “pirates” by the Greeks and Romans who looked down on Etruscans and saw them as “effeminate”. However, Etruscan Scholars are passionate to speak about Etruscan influence on ancient Rome and the Italian Peninsula. This is a big piece of discourse that is really important for this essay, because scholars believe that a lot of Greeks and Romans mirrored their Gods after the Etruscan pantheon. Of course, there is also debate about that, too. While most researchers believe that the Etruscan pantheon is older than the Roman and Greek pantheon, others conclude that Romans, Greeks, and Etruscans all influenced each other equally. Excavations and findings of ancient Etruscans and their lives are still ongoing to this day, and as Franceso Bonavita, Ph.D. says in his presentation titled The Etruscans: Who Were They?, “the presence of the Etruscans is ubiquitous.”

The Mesopotamian, Babylonian, and Egyptian cultures and religions also influenced the Italian Peninsula, especially when it comes to medicine, hygiene, and funerary rites. There is also some speculation that there also may have been some Nordic influence as well, which is something that I will also touch on in this essay. I’m not sure if I totally get behind this idea, but it does make sense since the Vikings were said to come to other lands on ships, and the comments about Etruscans being “pirates” could be an allusion to this. However, if the Etruscans did arrive in the ancient Italian Peninsula by boat, it was not for adventure or conquering. One possible origin of the Etruscans is that they may have been refugees from another land that was under attack, and escaped by sea.

It can be quite confusing to parse out which aspect belonged to which culture and civilization without an extensive academic background- which I do not have. For that reason, I am writing generally on the ancient Italian Peninsula with the focus on Etruscans and their pantheon, but I will briefly touch on the previously stated cultures to bring some context to Etruscan life. Scholars, anthropologists, and archeologists are fascinated with decoding their language, lifestyle, and origin. There is a small amount of information to glean on, and most of it is through conjecture, thus the Etruscans still remain a great mystery.

Here’s what we learn:

Etruscan Heaven, Underworld, and Religione

Etruscan Fate Goddess Nortia and The Ritual of The Nail

Etrusca Disciplina

Devotees of Hydrotherapy

Medicamenta and Herbaria

Etruscans, Their Medicine, and Babylonian Astral Magic

The Burlington Herbal: An Herbal Text of Renaissance Italy

Tyrrhenia, A Land Of Sorceresses and Drugs

Femme Healers of The Ancient Italian Peninsula

The Etruscans: Still A Mysterious and Ubiquitous People

Before Constantine the Great converted to Christianity, and the Roman Catholic Church was established, the Italian Peninsula was a place that saw many different types of religions and culture since before written history. Various cultures traveled through ancient Italy, some even impacting the modern Italian genome, as well. It has been speculated that what drove nomadic tribes to the Italian Peninsula was its remarkably fertile and lush soil [1]. The Etruscans, who are thought to be the indigenous people of Italy, thrived during the Villanovan Era, controlled a considerable portion of Italy, and founded the city of Etruria [2]. This ancient city is what we know now as Tuscany. It has been speculated that the Etruscans were extremely wealthy folk who cared deeply for their people and environment [79]. There have been many accounts stating that Etruscans called themselves Rasenna, Rasna, or Raśna. Greeks called them Tyrrhenians, and referred to the land they inhabited as Tyrrhenia. Some reports state that this word comes from the name Tyrsenos, son of Atys, king of Lydia, who led the first Etruscans to the region now called Tuscany. Other reports say Tyrrhenia comes from the Egyptian word Teresh meaning Sea People [96]. Although anthropologists’ and archeologists’ accumulated knowledge of the Etruscans are limited, what we can hypothesize from studying them is that they influenced ancient Rome and the Italian Peninsula. Etruscan written language has very little similarity to any Indo-European language [3], thus scholars can only make educated comparisons to any culture that might be slightly akin to decode their writing. Because of this, learning about their daily lives, political opinions, moral codes, and religious beliefs can be difficult to interpret. Eturia did not have one singular king, but instead was set up by many City-States where there were rulers of each region. However, the first three kings of Rome were Etruscan, and these kings brought with them highly skilled architects and scholars [4]. Eventually, after many warring years, the Romans overthrew the Etruscans, and they were assimilated into Roman culture and society in the 4th century BC. However, Etruscan influence would go on to shape an extensive part of, not only the ancient world, but the medieval world and our modern world as well.

Etruscan Heaven, Underworld, and Religione

Ancient Etruscans were passionate polytheists and animists [11], meaning they worshiped many Gods, and also viewed concepts, objects, and the environment in which they lived in to have its own representative deity that was also worshiped. This could mean that their relationship to the plant world and nature was also exalted into a personified God-like form, or represented by a deity of Land and Agriculture. We will touch more on this later. Etruscans were known as an intensely pious race of people, and had various rituals, rites, and observances that took prominence in their lifestyle [10]. Everything in Etruscan life reflected their deities, both greater and lesser, who had a big part in intervening in everyday life. They consulted the Gods before doing anything, and believed the Gods had a divine plan for everything. The word for God was ais or eis, and the plural was eiser, which looks strikingly similar to the Nordic word for God, “Æsir” [97]. Their God of Healing was Paeon, who was also known as the Doctor of the Gods. Because Etruscans, Greeks, and Romans persuaded the shape of each others’ religion and culture, Paeon became an epithet for Asclepius, the Greek God of Healing. Paeon also became an epithet for the Greco-Roman God Apollo, who could both bring disease and heal disease [9]. Apollo had an association with an older God named Helios, the Greek personification of the Sun, and therefore was also linked to Paeon, but was probably invoked by the name of Paion [8]. The Etruscan equivalent to Helios was Usil, another Solar God [94]. Tiv, whose name meant “Shining One”, was the Etruscan deity of the Moon, and was neither male nor female [98]. Most Etruscan Deities had their Greek and Roman counterparts in the Greco-Roman Pantheon, however Etruscan deities had names that were gender-neutral, as they switched sexes, and were often referenced as if a deity was an amalgamation or assembly of many energies in one [88, 95]. Tinia was comparable to Zeus/Jupiter, and he wielded three blood-colored lightning bolts [89]. Uni, Tinia’s wife, was associated with Hera/Juno. Menrva was the daughter of Tinia and Uni, and was the counterpart to Minerva/Pallas, the Goddess of War and Healing. Sethlans was the Blacksmith God who was associated with Vulcan/Hephaestus. Nethuns was also the God of Oceans who we recognize as Neptune. Voltumna, who was possibly the equivalent of the Roman God of Seasons Vertumnus or Vortumnus, was an agrarian God of the Underworld [90]. Voltumna was perceived as being the Supreme God of the Etruscan pantheon [91]. There was also what seems to be an endless list of lesser Gods, local deities, ancestral-hero spirits [lares], restless trickster and evil spirits [lemures], protector spirits, and more [24].

All of these deities were worshiped for different reasons, but were an important part of Etruscan life. As it relates to the original Etruscan origin myth, sadly, Etruscan literature has not survived. Anything involving the pantheon and the mythological stories can only be interpreted through artifacts like engravings on bronze mirrors [81]. Although it appears that the Etruscan pantheon reflects the Greek and Roman pantheon, it would be foolish to definitively say that these deities and myths are the complete replica of each other. For example, the story found on the mirror from Volterra depicts a connection between the Mother Goddess Uni and Hercle, the Etruscan Hercules [82]. In this mirror, Uni is nursing the adult Hercle. Present on this mirror are many deities, but among them is Tinia who is pointing to an inscription on the mirror: "eca: sren: tva: iχnac hercle: unial clan: θra:sce" which can be translated to “this picture shows how Hercle became Uni’s son” [83]. There are many interpretations of this engraving. One being that it is possible the Etruscans viewed that this adoption of Hercle, who is of Greek origin, could be understood as Etruria and Greece reconciling. Another explanation could simply be that this is a scene in which Hercle is being exalted into Godhood [84].

Tinia, Uni, and Menrva make up the Etruscan Trinity, just like the Roman Capitoline Triad Jupiter, Juno, Minerva [85]. Because Uni was a Supreme Mother Goddess of Reproduction and Fertility, it is surmised that Uni played a more significant role than her Juno counterpart did for the Romans [86]. Uni had her own temple, and was worshiped individually and at these shrines. Menrva, the Goddess of War, Art, Wisdom, and Medicine, is comparable to Athena/Minerva. In her authentic Etruscan version, she is illustrated as one of the lightning-throwing gods. However, the Greek Athena was never connected to weather [87]. We will shortly discuss how important lightning and thunder was for Etruscans.

Their religion put heavy emphasis on the afterlife. Many of the artifacts left behind were from their ancient tombs, where the walls of these burial places were vibrantly painted with scenes of parties, laughter, and gatherings. Sitting on top of the sarcophagi were sculptures of the deceased reclining as if to depict the person was alive, involved in the gatherings shown on the walls, and having a good time. Some researchers believe that the Etruscans felt that the afterlife had more significance than their mortal lives, and they further believed that the way someone was buried affected how their life after death will be. Another culture who felt the same about the afterlife were the Egyptians, who also decorated their tombs with vibrant depictions of the deceased in the afterlife. There were many designated Etruscan deities that guided souls into the afterlife like Charon, the psychopomp ferryman of Hades, and Vanth, a bat-winged chthonic goddess-like psychopomp who was the personal guide into the land of the dead. There were also angel-like spirits in the underworld that are described much like the valkyries of Valhalla in Norse myth. Because there is no Rosetta Stone to help us translate any of the Etruscan literature left behind, we do not have a full understanding of the how these Gods and spirits played into their origin myth, how they viewed flora and fauna, and what place or role they believed the Etruscan person played in the universe. Archeologists have done their best to compare bilingual literature, art, tombs, and artifacts found.

The Zagreb mummy, a mummy of an Egyptian woman wrapped in linen wrappings that were filled with Etruscan words, may present some clues. These linen wraps are believed to be a book of some kind, written in Italy between 200 - 150 B.C., and it is the longest and extensive Etruscan literature found to date [92]. After many years of trying to decipher this text, archeologists and scholars believe that these wrappings illustrate that there were many Gods, and that the Etruscans followed a ritual calendar in which they would enact certain rituals throughout their year [93]. Because the Etruscans were extremely spiritual, each part of the year was dedicated to a deity with its own ritual, libation, and offering. Yet, a question still remains: why was a lengthy Etruscan text buried with an Egyptian woman? Was she an Etruscan living in Egypt? Egyptians buried their deceased with their Book of Dead, so was this woman honoring possibly two ancestries, both Etruscan and Egyptian? Similar to how we take DNA tests to remember where we came from, was this a way to remember where she came from when she reached the afterlife? Were people of that time interested in their own ancestral origins? Or, lastly, could this have simply been entirely part of an Etruscan burial rite of her time, knowing that Etruscans share some cultural likeness to Egyptians?

Etruscan Fate Goddess Nortia and The Ritual of The Nail

When I originally wrote this essay, I looked everywhere for any kind of Etruscan Fate Deity, but could not find information on a being that would have rulership of fate and destiny. It was only when I revised this essay so I could post it on this blog that the Goddess Nortia came into view. I have written an entire blog post about my resonance with the Fate Deities of my ancestry, and have had many friends throughout my life who are Priestesses and Deity Workers refer to me as “The Oracle'', “The Seer”, Moirai, Völva, Nornir, etc. My entire life I have been protected by an Unnamed Goddess with Saturnian association who, when meditating and working with her, likes to refer to herself as “The Grim Fate”, among a few other names. You can check out that blog post here. Of note: I make association with my Patron Goddess Lua Saturni/Lua Mater to Fate Deities, and there may be further connection with this Ancient Italian Goddess Lua and the Etruscan Nortia.

Although both goddesses were worshiped in the winter months, with Lua being revered during Saturnalia alongside Saturn, Nortia, however, had her own ritual to mark the New Year. She was akin to the Roman Goddess Fortuna, and was the Patroness of the Etruscan city Velsna, which became the Roman City Volsinii [99]. In Etruria, the city of Velsna was sacred to the Etruscans, and it was so wealthy that Italian Naturalist Pliny the Elder describes the Romans wanting the “two thousand statues'' that stood in that sacred site as booty after their destruction of the Velsna [100]. Nortia and the God Voltumna both had temples in Velsna, and it was part of a new year custom to drive a nail into the beams of Nortia’s temple to mark the new year. Due to this ritual, Nortia is attributed to nails. Voltumna may have been Nortia’s consort, and as stated before in this essay, he represented the changing of seasons, agriculture, and plants. Nortia, with her connection to marking the number of Etruscan years, is similar to the Sabine Ops’ and Roman Rhea’s attribution to the flow of time, where Saturn, Ops/Rhea’s consort, was [still is] famously depicted as the Agrarian God of Time. Necessitas, the Roman personification of Fate, whom I referenced in my previous blog post, was also associated with nails. Augustan poet Horace illustrates the Goddess Fortuna/Necessitas: “the adamantine nail / That grim Necessity drives”. A 4th-century writer and native of Volsinii, Postumius Rufius Festus Avinenius, left behind a prayer to Nortia in an Umbrian Sanctuary in Hispellum:

“Nortia, I venerate you, I who sprang from a Volsinian lar [remember a lar is an ancestral hero spirit], living now at Rome, boosted by the honor of a doubled term as proconsul, crafting many poems, leading a guilt-free life, sound for my age, happy with my marriage to Placida and jubilant about our serial fecundity in offspring. May the spirit be vital for those things which, as arranged by the law of the fates, remain to be carried out.”

Lua Saturni/Lua Mater is associated with blood and rust. Again, I invite you to read the blog post I wrote about her in detail [as well as how her myths can help us through this Saturn in Pisces transit]. However, the symbology of rusty nails is also linked to Lua. The protection over purified objects and weapons after war is why she was invoked in the Ancient Italian Peninsula, and I liken it to purifying and ending a cycle of karma after bloodshed.

The Etruscan Athrpa, eerily identical to Atropos, one of the Moirai or Fates of the Greek Pantheon, is depicted on the Etruscan Bronze Mirror. She is winged, and holds both the hammer and nail in her hands. I find these connections to excite every fabric of my being, as I feel a sense of peace in the arms of my protector Goddess, who was Unnamed my entire life, come into clear vision for me on a deeply soul level. It seems that the driving of a nail into a beam was part of a ritual in which a point of time was fixed or immovable. The Oxford Dictionary defines fate: “the development of events outside a person's control, regarded as predetermined by a supernatural power.”

In Italian and Sicilian culture, the spell and incantation to dispel the malocchio must be passed down to a family member on Christmas Eve. However, I remember my grandmother asking for an iron nail on New Years Eve, close to midnight. Unfortunately, my mother could not find one, but had an old iron key. My grandmother used this iron key to draw a cross on the crown of my head, and she whispered an incantation. At the time, my grandmother was beginning to enter a phase of her life where she endured undiagnosed dementia and Alzheimer's. I am making a note of this, because I believe she merged three ancient rituals together, possibly accidentally: one that marked the New Year with a nail, another in which she was passing down the gift to dispel the malocchio [albeit on the wrong day of the year], and another one that relieves a child of demonic activity or ill-will. Or maybe my grandmother was like me, and was a little rebel magician, and meant to mark my New Year free of malochhio, evil, and ill-will.

Etrusca Disciplina

The Etruscan sky was divided up into 16 regions, and these divisions were attributed to the specific deities of the Etruscan Pantheon, as depicted on the the Liver of Piacenza [15]. Found in the province of Piacenza, Italy, the Liver of Piacenza is a life-sized bronze model of the liver of a sheep [21]. The liver is divided into 16 sections, or houses, and the names of the Etruscan pantheon are inscribed within each section, depicting where each deity holds reign in certain cardinal points and seasons [16]. Although archeologists and Etruscan scholars are still trying to decipher the meaning of this artifact, they are convinced that these sections on the Liver of Piacenza can also be projected onto the sky, and were most likely used to teach others in their community about their Gods [17]. Some argue that it could very well be a representation of constellations or astrological signs, despite the lack of evidence. It is my personal belief that it could have been an astrological, astronomical, and pantheon projection of their sky. Meaning, each deity may have had an astrological influence, especially during certain times of the year, just as our modern and medieval astrology does. Regardless, this model was an illustration of the way they viewed the cosmos.

Etruscans built sacred temples facing the direction in the sky where a specific God ruled or resided according to the Liver of Piacenza [18]. There is speculation that Etruscan “heaven” was subject to the sky’s movement according to the seasons, and the Liver of Piacenza was rotated clockwise or counterclockwise depending on the position of sunrise and sunset on the solstices and equinoxes [19]. The temples that were built to honor specific Gods were “empty” when not in position with the sky due to the change of season, but when aligned, it was said that the God of that temple could and would “visit” from the sky [20]. The Liver of Piacenza was read by the Haruspex, the most exalted figure in the ancient Etruscan community. The Haruspex had both their place in the royal courts, as well as their local communities, and they were physicians, healers, teachers, and diviners [36]. The Haruspex had the ability to see the future, diagnose illnesses, decipher omens, and know when to plant crops from examining the entrails of sacrificed animals [21]. Hepatoscopy, or haruspicy, is a form of divination by inspecting omens found on the liver of sacrificed animals [23]. With this information, we can connect the Etruscans to the ancient Chaldeans of Mesopotamia and/or the Anatolians of Babylonia, who were the originators of Hepatoscopy [22]. The Romans called this specific practice of divination “Etrusca Disciplina” or “The Etruscan Discipline” [31]. Brontoscopy, a form of divination by deciphering the omens found in the sound and appearance of thunder and lightning in certain regions of the sky, also has its origins in ancient Babylonia [32]. This practice was crucial for Etruscans, because they felt that through thunder and lightning, their celestial Gods and Goddesses could express their feelings to earth–bound mortals. The placement of the thunder was important, and was read by the haruspex according to the Liver of Piacenza. For instance, if the thunder was found to strike in the North-West part of the sky, it was a terrible omen. The Northwest was the region ruled by Satre, a dangerous chthonic Death-God of the Etruscan Pantheon, who may have some correlation to the Roman God Saturn [33]. This inscription can be found on the Liver of Piacenza.

Devotees of Hydrotherapy

Research goes back and forth on agreeing that Etruscans may share DNA with modern day Turkey. Other research points to Germanic descent. Regardless, the DNA testing to come to these results are done on modern-day living people in Tuscany. However, if we are to draw upon the speculation that the earliest of the Etruscans could be of Mesopotamian or Babylonian origin, then we can look to their relationship with water. “Asu” is the ancient Babylonian word for physician, and it means “one who knows water” [12]. Etruscans wholly revered wells, and thought protective deities watched over them. These specific deities had to be acknowledged and respected. Water was such a critical component and element in Etruscan lifestyle. In his article, The Etruscans and their Medicine, Ralph H. Major says that the Etruscans were “devotees of hydrotherapy and constructed extensive baths” [13]. While Romans had large baths that could house upwards of 8,000 people per day, the Etruscans also had baths, but on a smaller scale and separated in three distinct pools: frigidarium [cold water], tepidarium [tepid water], and caldarium [hot water] [7]. These pools had distinct uses for specific ailments. Furthermore, the Cloaca Maxima, the most well-known and largest sewer in history, was created in the reign of Etruscan King of Rome, Tarquinius Priscus [600 B.C] [14], and was named after the Goddess Cloacina who protected the sewers. There were clear distinctions and intentions in their utilization of water: Etruscans knew that clean drinking water was a necessity for their well-being, they utilized the temperature of bathing water and understood different temperatures had specific uses for the body, they recognized the appropriate disposal and drainage of sewer water was fundamental, and they cherished the sacred deity they believed dwelled within water. “Devotees of Hydrotherapy” indeed. With this information, we can conclude that the Etruscans practiced personal hygiene, as well as water worship.

Ancient Egyptians also highly valued cleanliness to prevent people from dying due to illness. Because Mesopotamia and Egypt influenced each other, and they influenced Greeks, and Greeks and Etruscans influenced Romans [and vice-versa], we can see how the significance of sanitation kept up through time and throughout these cultures. Romans, Greeks, and Egyptians saw contracting an illness as punishment from the Gods as a consequence of sin or crime. In my opinion, it seems that cleanliness wasn’t only a way to prevent disease, but it was a way to remain spiritually pure in the eyes of their Gods, respectively. Illness was a “sign” that the Gods were angry, and appeasing the Gods was part-and-parcel of the healing process. Healing was seen as a gift from the Gods, as well as their forgiveness. Given the evidence we have about how devout and spiritual Etruscans were, and how often they sought connection to their Gods, assuming the Etruscans felt the same way about disease and healing could be a safe theory.

The Etruscans had a divinatory practice that employed the use of water called lecanomancy [34]. The Greek word “lekane” means “basin” in English. Oil was poured in a basin of water, and by observing the shapes made from the separation of the oil from the water, the prediction could be translated. This type of augury would look familiar to distant and contemporary Sicilians and Italians alike. In Sicilian, Italian, Sicilian-American, and Italian-American cultures, diagnosing and dispelling the evil eye, or malocchio, involves pouring oil into a small bowl of water and depending on the configuration the oil takes on, the malocchio could be properly handled by the local healer.

Medicamenta and Herbaria

All Roman and Greek medicine was administered as part of a healing ritual of some kind, and where modern society may view this as performative or superstitious, these ceremonies and rituals were part of the medicinal and healing process, and very much welcomed in Ancient Rome [49]. Incantations were spoken while dosing, as it was believed words held “magic” powers, just as much as the herbs and plants did [54]. Romans were cautious of Greek medicine, and often saw them as charlatans [55]. This is possibly due to the very many different cultures that inhabited the Italian Peninsula at the time. Greeks distrusted Etruscans, Romans distrusted Greeks, and so on and so forth. This division among the people of these regions developed into nationalism, and transformed into a desire and need to document or identify their own social, religious, scientific, medical, and political views through written encyclopedias and pharmacopoeias [61]. Sources for Roman folk medicine, or medicamenta, reside in the recipes in Cato’s written work on agriculture, Celsus’ treatise, and Pliny the Elder who wrote about nearly a thousand medical herbs, as well as various animal parts [50]. According to Pliny, a cure for a headache was the following: water left from the drink of an ox, the genitals of a male fox tied around the head, the ashes of a stag’s horn applied in vinegar or rose-oil [Pliny XXVII 166] [51]. Capsules, or pastilli, were typically used with crushed herbs and a type of metallic ingredient [75]. Take for example, Celsus’ capsule recipe for coughs: myrrh, pepper, saffron, cinnamon, poppy tears, costmary, galbanum, and castoreum [76], an exudate from the anal gland sac of beavers. Castoreum was used in perfumes, drinks, and beverages throughout the 1900s in various parts of the world when chemists discovered the taste was akin to vanilla [78]. Perhaps the use of castoreum for the modern chemist was the same for ancient Romans: it was used to cover the taste and smell of overpowering fresh herbs.

Some food items were also used as medicine like oil, milk, honey, wine, fats, and vinegar [52]. Goat and cow milk was used for healing, but so was human milk. Milk therapy stretches all the way back to Ancient Egypt, and was used in Greece and Rome, but all cultures were very particular about what milk was used. For instance, a woman who produced milk after giving birth to a male child was utilized exclusively [53]. It’s hard to say if this was a type of therapy the Etruscans used, as we have no evidence either way.

For a toothache, Celsus recommends pulling mint from the roots, pouring hot water over it while the patient inhales the steam with an open mouth [56]. The analgesic and antiseptic properties in mint could have been a quick relief for the ancient Romans, and we still use mint for pain relief today. For epilepsy, a purge of black hellebore was recommended, followed by a light diet where meat, especially pork, was forbidden, avoiding stress and fatigue, and alternating cold and hot baths [57]. Hellebore, which has a chemical constituent similar to our drug Digitoxin, may help the heart beat regularly. This could have been helpful to the Romans who were experiencing epilepsy due to irregular heartbeat.

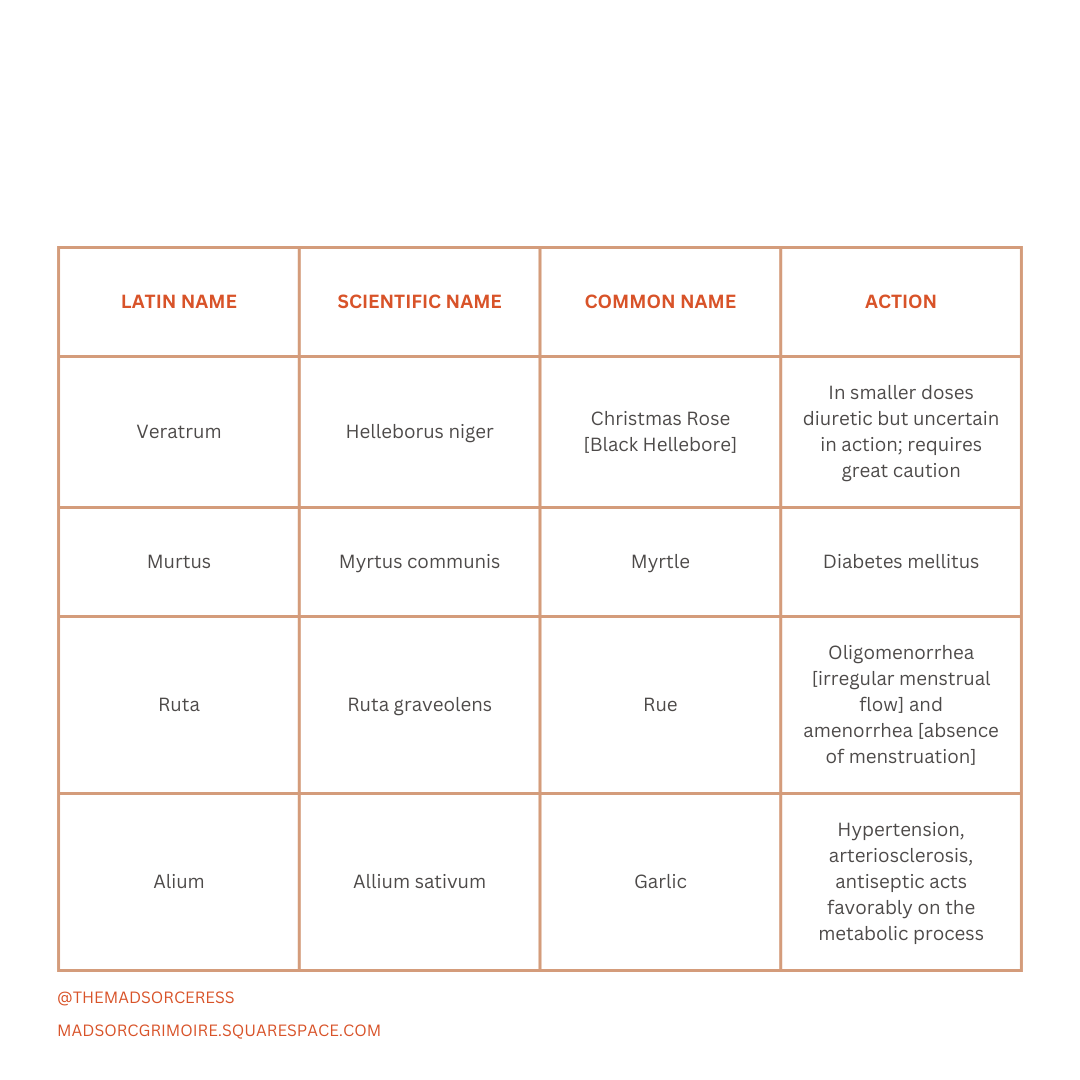

Many amulets made from animal parts and herbs like dill were also used [58]. Across many cultures, amulets held protective spiritual significance in the industry of healing, as the Roman belief was that certain diseases, especially epilepsy [comitialis morbus], was caused by demonic possession [59]. Dioscorides of Anazarbus describes in his work in the 1st century CE, Materia Medica, that wearing an amulet made of green jasper can help alleviate stomach pain [80]. I am adding a brief example table of some of the medicinal plants for cardiovascular therapy according to Pliny [60]:

Etruscans, Their Medicine, and Babylonian Astral Magic

Regarding Etruscan medicine and herbaria, there is no surviving Etruscan Herbal text or manual. However, Mesopotamian and Babylonian Herbals have survived, and even one Italian Herbal has been preserved from the Renaissance period. Recall that Etruscans, Mesopotamians, Babylonians, and Italians may have cultural connections. In Assyrian Herbals, each plant and vegetable was classified in categories. The first category is titled with “u”, which is the Sumerian word for “herb”, and it is followed by the category titled “sar”, which means plant [37]. Greek herbals also make a distinction between medicinal plants and vegetables [38]. Many scholars believe the term haruspex was also applied to astrologers and astronomers, who were also known as “experts of celestial matters” [35]. Further evidence of this can be found in studying the Babylonian herbals. In these herbals, directions are indicated for concoctions or medicines to sit overnight under the stars before applying or administering it to the patient [25]. Whether this was merely an instruction due to the fact that most, if not all, herbal medicines should be infused for some time, or if there was possibly a strong belief in the astrological energetic magic that could be infused into the medicine, is up for debate [29]. However, it appears that Babylonians did believe in Astral Magic, and put their faith in the Gods that ruled over certain constellations [26].

The constellation Lyra, with its fixed star Vega, was associated with the restoration goddess named Gula, who was depicted alongside goats and dogs [27]. She was also known to the Akkadian people as Ninkarrak, and as Ninisina to the Sumerian people. Gula was a goddess very similar to the Greek Hekate and Anatolian Hecate, who was Goddess of The Underworld, Poisonous Herbs, and Magic. Vega was associated with healing, and many medicines were left overnight under this star accompanied by a circle of protection traced around it [28]. The protection circle was drawn around the concoction to keep evil energies away from it, so that the healing quality of the medicine was preserved, and could be utilized [30]. This belief that plants could have “malefic” or “benefic” energetics within them could also be found in an ancient Italian Herbal called The Burlington Herbal.

The Burlington Herbal: An Herbal Text of Renaissance Italy

Found in Tuscany, Italy, and preserved in Burlington, Virginia, this Herbal illustrates the medical philosophies of Northern Italians in the year 1500, and includes hand-drawn pictures of plants, demons, angels, and other spirits [39]. For Italians of this time, “witchcraft” and magic were taken into account when dealing with sickness and disease [40]. This ideology could stretch all the way back to when the predecessors of the Italians of the Renaissance believed that disease was punishment from the Gods. Physicians were taught that medicinal plants had energetic signatures of angels and demons depending on which herb was used [41]. Some herbs even had the power to chase demons away [42]. Physicians of this time would have been well-versed in astronomy, astrology, and the occult [43], which only bolsters the evidence that the Haruspex, the Etruscan soothsayer and physician, was also fluent in astrological and astronomical subjects. In the drawings of this Herbal, angels are guiding people to specific plants to cure the ailment or disease in question [44]. One could either conclude that these illustrations were alluding to the fact that they believed plants either could guide the sick to a particular plant through intuition, and/or they thought plants had spirits of their own. It is my understanding that a hypothesis like this could further validate the theory that ancients of the Italian Peninsula were animists, and had a passionately spiritual relationship with nature. Classifications and names of plants varied from region to region in Italy, and this would make sense since each region of Italy had, and still has, its own dialect [45]. This fact alone creates confusion, and makes it difficult to identify each plant with the modern eye. On top of the regional dialects and names, mistakes were also made in plant identification, and even the new research of today changes plant classification.

Tyrrhenia, A Land Of Sorceresses and Drugs

To reiterate, no tablet, document, or text of Etruscan medicinal content has been found. However, the knowledge we’ve gained from Etruscan Medicine comes from what Ralph H. Major terms as “external evidence”:

“Theophrastos, the father of botany, states in his Enquiry into Plants, ‘Aeschylus, too, in his elegies speaks of Tyrrhenia as rich in drugs, for he tells of the ‘Thrrehnian stock, a nation that makes drugs’.” Aside from this reference, we know nothing of the drugs they employed, but we can be reasonably sure they had a rich materia medica.”

In Renaissance Italy, women could become a licensed practicing herbalist and physician, however they were not allowed to attend a university to learn. They could, however, be taught by their husbands or fathers, and then go on to practice [60]. In Etruria, it was possibly a different story as anyone could become a physician and no qualifications were necessary. Etruscan women were seen as equals among their male counterparts [47], and therefore were most likely able to become physicians. In contrast to the Greco-Roman society, where women were not seen as equal, Etruscans were “othered”, and seen as both somehow “barbaric” and “effeminate” [48] due to their unbiased view of the women in their communities [46]. Larissa Bonafonte Warren reiterates what the 4th century B.C. Greek historian Theopompus details about Etruscan women in one of his reports:

“Differences between Etruscan and Greek women were striking. Theopompus, the Greek historian of the fourth century B.C., was startled by them, and drew the worst possible conclusion from what he saw and heard about Etruscan women. According to his report, they took great care of their bodies, often exercising in the nude with men and with each other; it was not considered shameful for women to show themselves naked. They were very beautiful. At dinner, he tells us, they reclined publicly with men other than their husbands. They even took part in the toasting - traditionally reserved for men and regulated by strict formalities at Greek symposia. Etruscan women like to drink (so, by the way, did Greek women, according to Aristophanes and others. This is the most familiar accusation of immortality). Most shocking of all, they raised all their children, according to Theopompus, whether or not they knew who the fathers were. [...] That women exercised together with men in the nude, in either Athens or in any Etruscan city is patently untrue. Etruscan women did join men publicly in watching sports, a custom most un-Greek [...]. They apparently were not, however, particularly fond of such strenuous exercise as spartan women practiced, nor did they ever appear naked. As for exercising in the nude, even Etruscan men normally wore shorts, heroic nudity being a peculiarly Greek invention in the ancient Mediterranean world. It was practiced by Greeks alone [...]”

Furthermore, I came across a review written by Jessica Lightfoot on Circe, the Sorceress in Homer’s Odyssey, which I found interesting and relevant to this essay. While we do not have any proof of how Etruscan women used herbs, or what herbs were used at all, this may shed some light with, once again, external evidence:

“If we examine the broader Theophrastan passage in which the fragment is embedded it becomes clear that Aeschylus’ words are being used as evidence in a complex argument which connects Homer’s Circe, and the powerful drugs which she uses to transform Odysseus’ men into swine, to Tyrrhenia in Italy, the home of the Etruscans. This connection is also found in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History in a passage which uses the same Aeschylean poem as evidence for Circe’s association with Italy. Circe’s homeland of Aeaea is not mapped onto a real-world Italian location in Homer’s poetry, though this localisation appears later in the Greek literary tradition, most notably at the end of Hesiod’s Theogony. By carefully examining both the passages of Theophrastus and Pliny in which Aeschylus’ words are mentioned, it is clear that his original elegiac poem also refers to Circe’s localisation in Italy, and to her status as the supposed ancestor of the Etruscan people as the mother of Agrius, Latinus and Telegonus, three Italian sons purportedly born to Odysseus. Aeschylus’ elegiac fragment is thus the earliest text we have that links Circe’s drugs to Italy, and one of the very earliest extant references linking Odysseus’ famous travels to the Italian mainland. As such, it presents us with crucial and hitherto unappreciated early evidence concerning interactions between Greeks and non-Greeks in the western Mediterranean.”

I cannot pretend to draw my own definitive conclusions and connections, but I do find this fascinating. If, however, we take this piece of information, paired with Etruscan Hydrotherapy, their devoted and daily spiritual connection, the equality between men and women, and the rumors that Tyrrhenia was a “drug-making” land, it is possible that Etruscan women had an extensive expertise in medicine, healing, and nature, but were perceived as taking a “sorceress” or “high priestess” approach from an outsider’s perspective. Alternatively, it could be yet another story to “other” powerful Etruscan women by simply stating that a woman with herbs is a witch who has the ability to do awful things to men, just like so many suspicious and fearful men have claimed in so many cultures across time.

Femme Healers of The Ancient Italian Peninsula

There were so many amazing masc physicians, astronomers, astrologers, occultists, and soothsayers of ancient Italy, however, these figures have been celebrated for centuries, and many essays have been written about their contribution to medicine. On the other hand, we have very little documentation on femme physicians before the Renaissance.

In the first century, Antiochis of Tlos, daughter of Diodotus of Tlos, was a physician that dealt with disease of both men and women [66]. She lived in what was known as Anatolia, now known as Turkey [67]. In the Middle Ages, Italian Noblewoman Dorotea Bucca, who lived between 1300-1400, was actually a professor at the University of Bologna. Trota of Salerno, who lived around 1100 in the southern Italian coastal town called Salerno, was a highly regarded physician [63]. She dealt mainly with the female reproductive system, and wrote a document called De curis mulierum [On Treatments for Women] [64]. She was educated in the Medical School of Salerno, which happens to be the world’s first medical school [65]. There may have even been a figure called Cleopatra Metrodora, who lived in the seventh century AD in either Egypt or Greece [68, 69]. Metrodora was a progressive gynecologist, midwife, and surgeon who was ahead of her time. She wrote many works, one of them titled On the Uterus, Abdomen, and Kidneys [70]. She had the ability to determine the sex of a fetus, constructed a tampon-like device made from potato porridge and goose fat, and apparently was skilled in facial reconstruction [71].

Etruscan women had a right to raise their children without the child’s father, and especially without the judgment of Etruscan society [72]. It has also been speculated that because the Etruscans were so wealthy, there wasn’t food scarcity or a need for population control [73]. Therefore, children were raised by the entire community without resentment [74]. Given what we know thus far, whether rumored or factual, about the lives of Etruscans and their relationship to their environment and community, it is safe to say that Etruscan women also practiced medicine, or at least knew enough to self-medicate and treat their children’s illnesses. In addition, recall the animistic perception the Etruscans had paired with their inherent ability to connect their environment, their emotions, and the elements to the divine. In my opinion, women, men, and children were most likely taught to learn about their local botanicals, how to use them for various reasons, what deities were associated or prayed to per each plant, how to heal themselves with a specific herb, and definitely how to revive and treat anyone with an illness in their community.

The Etruscans: Still A Mysterious and Ubiquitous People

To reiterate, there simply isn’t enough information left behind by the Etruscans to get the full picture of how they approached their way of medicating through the use of herbs, but putting the pieces together is what makes studying the Etruscans so captivating. We are able to make educated conclusions from artifacts, and we can still cross-reference with cultures of their time that were similar and shared land, trade, resources, art, and stories like the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, Mesopotamians, and Babylonians. I take comfort in knowing that these people, both constantly seeking contact with their Deities, as well as seeing the “spirit” in all things, would have greatly respected their environment and elementals, animal friends, and especially their herbal neighbors. It is highly likely the animals and botanicals would have had their own designated deity and spirit resided within, and were associated with them. To me, the Etruscans seem to play a key role in the appreciation and care of the land that is the Italian Peninsula, influencing the great Roman and Greek civilizations before their conquests. I believe this is a civilization not only worth investigating, but most likely needed: their approach to holding deep regard for every single aspect of life, and their unbiased equality and care for their communities could ultimately teach us how to consider and protect our own. Maybe one day more evidence will be unearthed and translated. For now, we are left with the mystery and omnipresence of the Etruscans.

Resources & Research Citing:

[1]: History of Italy Explained in 16 Minutes, Captivating History

[2, 3, 11, 24, 33, 47, 85]: Archaic Roman Religion, With An Appendix on the Etruscans, by Georges Dumezil

[4]: The History and Culture of the Etruscans

[5]: Loevy HT, Kowitz AA. The dawn of dentistry: dentistry among the Etruscans. Int Dent J. 1997 Oct;47(5):279-84. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.1997.tb00790.x. PMID: 9448810.

[7, 10, 48, ]: The Etruscans: Who Were They?, Presented by the American Italian Cultural Roundtable and Francesco Bonavita, Ph.D.

[8]: The Cults of the Greek States, By Lewis Richard Farnell

[9]: Apollo, by Fritz Graf

[10, 12, 13, 14, 21, 22, 23,]: Major, R. H. (1953). The Etruscans and their Medicine. Sudhoffs Archiv Für Geschichte Der Medizin Und Der Naturwissenschaften, 37(3/4), 299–306. The Etruscans and their Medicine

[15, 16. 17, 18, 19, 20,]: Stevens, Natalie L. C. “A New Reconstruction of the Etruscan Heaven.” American Journal of Archaeology 113, no. 2 (2009): 153–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20627565.

[25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 36, 37, 38] Reiner, E. (1995). Astral Magic in Babylonia. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 85(4), i–150. Astral Magic in Babylonia

[39, 41, 42, 43 , 44, 45] Silberman, H. C. (1996). Superstition and Medical Knowledge in an Italian Herbal. Pharmacy in History, 38(2), 87–94. Superstition and Medical Knowledge in an Italian Herbal

[46, 72, 73, 74, 79] Warren, L. B. (1973). THE WOMEN OF ETRURIA. Arethusa, 6(1), 91–101. THE WOMEN OF ETRURIA

[49, 50, 51, 52, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, ] JONES, W. H. S. (1957). Ancient Roman Folk Medicine. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 12(4), 459–472. Ancient Roman Folk Medicine

[5 ] Laskaris, J. (2008). Nursing Mothers in Greek and Roman Medicine. American Journal of Archaeology, 112(3), 459–464. Nursing Mothers in Greek and Roman Medicine

60, 61] van Tellingen C. Pliny's pharmacopoeia or the Roman treat. Neth Heart J. 2007;15(3):118-20. doi: 10.1007/BF03085966. PMID: 18604277; PMCID: PMC2442893.

[62] The Italian Patient: Health care in Renaissance Italy - OpenLearn - Open University.

[63, 67, 68] A History of Women Doctors

[64, 65] Trota of Salerno - Wikipedia

[66] Antiochis of Tlos - Wikipedia

[69, 70, 71] (PDF) Metrodora, an Innovative Gynecologist, Midwife, and Surgeon

[75, 80,] Roman Medicine - World History Encyclopedia

[78] From opium to beaver anal secretions, here’s what’s in your food | The Independent

[81, 82, 83, 84, 86 ] Uni (mythology) - Wikipedia

[88, 89, ] Tinia - Wikipedia

[91] Voltumna - Wikipedia

[92, 95 ] Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend

[96] Etruscan civilization - Wikipedia

[97] Etruscan religion - Wikipedia

[98] Tiv, Etruscan Goddess of the Moon

[99, 100] Nortia, Etruscan Goddess of Fate and Patron Goddess of the City of Velsna

The Ancient Origins Of The Roman Empire With Mary Beard | Rome: Empire Without Limit | Odyssey

Babylonian Liver Tablet | British Museum

Liver of Piacenza File:Foie de Plaisance.jpg - Wikimedia Commons